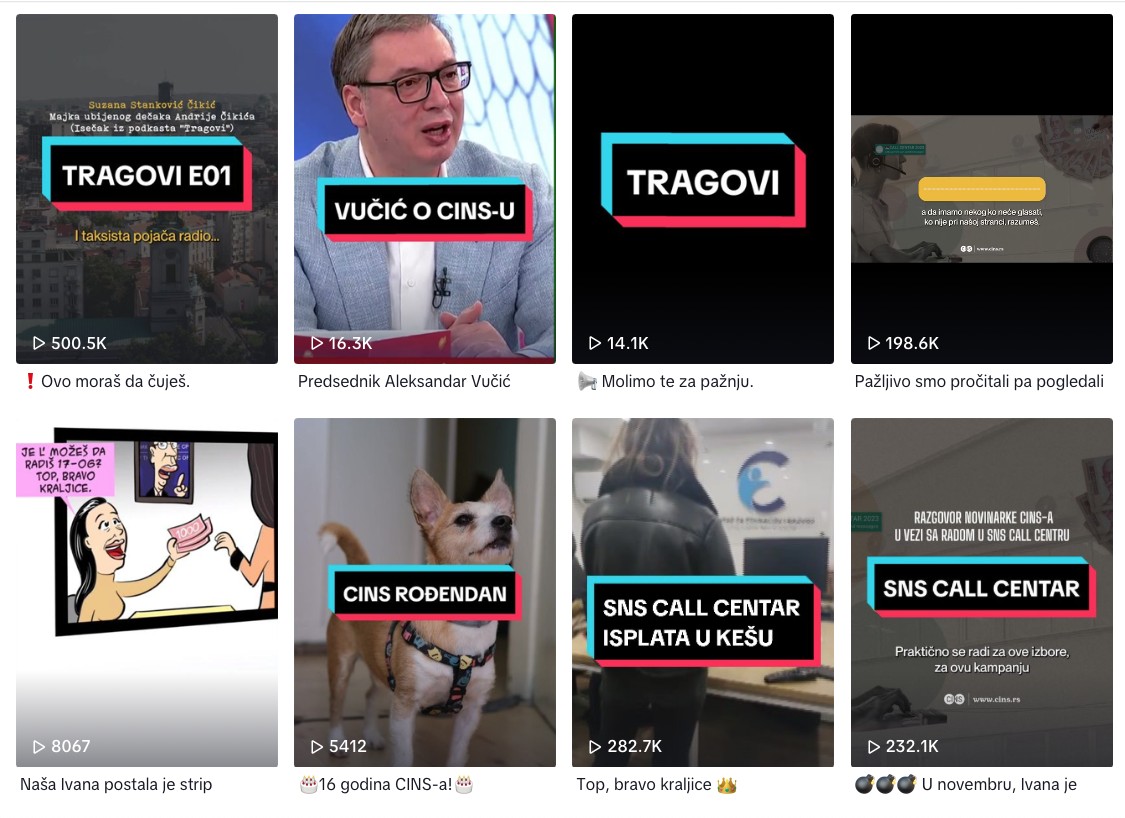

The award-winning Serbian Center for Investigative Journalism (CINS) has expanded the audience for its investigative journalism by reaching the public through non-traditional platforms like TikTok. Image: Screenshot, Tiktok, CINS

One of the call center workers was Ivana Milosavljević, a journalist from the Center for Investigative Journalism in Serbia (CINS) working undercover. In the heart of the operation, Milosavljević recorded video and audio footage and discovered how the campaign worked. “We were aware of the ruling party’s call centers, but we couldn’t have imagined how they operated,” Milosavljević tells GIJN.

The only requirement for getting hired, and eventually paid, was to express an intention to vote for the SNS on election day — December 17 — and to send proof after voting. The daily wage offered would also be much higher for working on election day. This arrangement suggested the party was engaging in vote-buying and “dark” campaign funding; offering a job or money in exchange for a vote is a criminal offense in Serbia.

“We don’t have as much reach as the national media… But these stories went out of that frame and spread so much.” — CINS Editor-in-Chief Vladimir Kostić

The decision to go undercover — an extremely rare reporting tactic in Serbia — required meticulous planning and debate. “It was difficult to make an editorial decision,” CINS Editor-in-Chief Vladimir Kostić tells GIJN. “We had to do a lot of research and talk with a source who helped us to create a map of the area itself, of all the people there… to finally make the right decision.”

To mitigate some of the ethical and security concerns of undercover reporting, they decided that Milosavljević would use her real name at the call center, and put other safety measures in place. “I deleted all my social media accounts, removed my name as an author from the CINS website, and we worked to erase as much of my digital footprint as possible,” Milosavljević explains. “We also consulted with a lawyer about how to handle any unforeseen situations.” A panic button system on her phone would alert her team in an emergency.

Watch a short YouTube video of CINS’ undercover investigation of a party call center in Serbia.

Serbia Votes

The investigation, CINS in the SNS Call Center: Agency for Hostesses, Buying Votes and Millions in Cash, was published just over two weeks before the December elections. It included screenshots from the call center WhatsApp group, audio recordings of a call between Milosavljević and the center coordinator, and video footage of a woman explaining how Milosavljević would send proof of her SNS vote on election day — when the day wage would be 9,000 Serbian dinars (US$83). This evidence revealed how cash — not declared as part of the campaign — was effectively used to buy votes for the ruling party.

According to Kostić, the story reached more than 3.5 million people — around half of the country’s population. This figure is a total of article reads, video views, and social media reach from their own channels, explains CINS Director Milica Šarić. She adds that because other media — including Serbia’s independent TV channel — and various activists shared it, they believe the story’s reach may have been even larger.

“Maybe we can restore trust in the independent media, since, like everywhere else in the world, interest in the media is in decline here.” — CINS Director Milica Šarić

“We don’t have as much reach as the national media,” says Kostić. “But these stories went out of that frame and spread so much. It [shows that] we have left the bubble range of our investigative media outlets.”

The elections brought the SNS a larger-than-expected victory and the party regained its parliamentary majority — but the legitimacy of the election results, particularly in the Belgrade municipality, was disputed by opposition parties and criticized by international election observers. The OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) reported widespread electoral irregularities and abuse of public funds, including instances of vote-buying, ballot-stuffing, and violence.

The OSCE/ODIHR’s final election monitoring report twice referenced CINS’s reporting — in its discussion of unsolicited phone calls from the SNS-affiliated call center and of third-party campaign funding, which remains unregulated. After the election, Serbia’s opposition parties formed a protest movement and filed a criminal complaint. Thousands protested for months against what they called a rigged election.

The reporters behind the investigation — Ivana Milosavljević, Teodora Ćurčić, and Vladimir Kostić have been recognized for their work, netting three Dejan Anastasijević Awards for Investigative Journalism in Serbia and the Ethical Journalism Award.

CINS celebrating members of its staff winning Dejan Anastasijević Investigative Journalism Awards in May 2024. Image: Courtesy of CINS

The reach and impact of their investigation have not, so far, translated into institutional action from the prosecutor’s office and anti-corruption agencies. “We expected much more from the state institutions to do something about it, but since we live in a captive society where institutions are controlled, it was important for us to show people what that actually looks like,” says Kostić.

“Maybe we can restore trust in the independent media, since, like everywhere else in the world, interest in the media is in decline here,” adds Šarić.

Following the protests and dispute over the December vote, the SNS agreed to a rerun of the Belgrade municipal election, which was held on June 2, along with other local and provincial votes. SNS won control of Belgrade municipality again. A subsequent OSCE/ODIHR election monitoring report noted that the June 2 elections were “well-administered,” but still marred by an “unjust playing field” that included media bias, widespread pressure on public sector employees, and misuse of public funds.

‘Multi-Pronged’ Challenges

CINS, a nonprofit and nongovernmental organization, was founded in 2007 by the Independent Association of Journalists of Serbia (NUNS) to produce world-class investigative journalism with innovative tools and methods. In 2012, CINS became an independent legal body. It is a member of both the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and GIJN, joining the latter the first year it became independent. It currently has a staff of eight, with five board members.

In 2017, CINS was awarded the European Press Prize in the investigative journalism category for its coverage of corruption and organized crime in Serbia and the links between soccer, politics, and crime. The same year CINS was a finalist for GIJN’s Global Shining Light Award.

To avoid influence from business and political interests, CINS is funded through donations. Roughly 90% of its revenue comes in the form of grants, with the rest of its income derived from direct donations or services like publishing, training, and research. “CINS is dependent on philanthropic support, mainly grants it receives in open calls for proposals,” explains Sarić. “This funding is unreliable and unpredictable, leading CINS to ask for support from individual donors who believe in CINS’s mission, while also working on revenue diversification.” Their future revenue strategies include providing journalism and fact-checking training, a targeted campaign to increase individual donations, and membership options.

“Although there is quality journalism in Serbia, awarded for its investigations into crime and corruption, it is caught between rampant fake news and propaganda.” — RSF’s 2024 World Press Freedom Index

CINS operates in a challenging environment that has deteriorated in the last decade.

The latest global press freedom report from Reporters without Borders (RSF) ranks Serbia 98th, the country’s worst position in 22 years, noting that there is rampant disinformation and propaganda and that with around 2,500 media outlets, the market is “highly fragmented.” CINS and other investigative independent newsrooms in Serbia, such as KRIK and the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN)’s Belgrade branch, are up against influential TV networks and tabloids with close links to the state. Freedom House describes Serbia as a “partly free” regime where “the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) has steadily eroded political rights and civil liberties, putting pressure on independent media, the political opposition, and civil society organizations.”

Journalists working in Serbia face multi-pronged harassment and repression tactics, including threats and attacks from politicians and gangs, smear campaigns by pro-government tabloids, and SLAPP suits — although Serbia ostensibly has robust press freedom laws. RSF also reported that journalists were confronted with widespread physical and verbal attacks during the June 2 elections.

“Working conditions of investigative journalists in Serbia are not at all easy,” explains Tamara Filipovic, project manager for the Independent Association of Journalists in Serbia (NUNS). “Apart from the threats they receive almost regularly, they are very often exposed to various types of pressure, such as targeting, insults, and belittling, which first of all come from higher government officials, and then spill over to the so-called ordinary citizens who also take some more drastic steps such as intercepting them on the streets, physical attacks or sending death threats.”

NUNS has been recording attacks, threats, and pressure on journalists in the region for years in two publicly available databases, bazenuns.rs and safejournalists.net. “The number of recorded cases this year is alarming. In the first four months, we recorded three times more such cases than in the first four months of last year, which worries us a lot,” says Filipović.

New Focus on Audience Engagement

To increase interest in the media and investigative journalism, CINS is expanding its focus on audience engagement, trying out novel forms and approaches to publishing not yet widely familiar in Serbian media. They have branched out into longform investigative podcasts, started promoting their work on TikTok, and gamifying their reporting. As part of this effort, in September 2023 Zoran Miodrag — who has experience in digital marketing — joined the team as a dedicated director of communications, in charge of CINS channels, promotion, and audience engagement.

The CINS longform investigative podcast Tragovi looked into two days of tragic mass shootings in Serbia. Image: Screenshot, CINS

In December 2023, CINS published an investigative narrative podcast reporting on two mass shootings over two days in May 2023 — one in a Belgrade elementary school and a separate incident near the capital the following day — that killed 17 people in total.

The podcast, titled Tragovi (“Traces” or “Clues” in English), was created by reporters Stefan Marković and Jovana Tomić, with editorial and post-production support. Editor-in-Chief Kostić recalls the challenge of reporting on the topic with traumatized families who also needed time to process what happened. “It was important to us that the story was not about the boy who committed the murder, but about what happened to us. It is a story about the system, and the story of those families,” he explains.

This shooting sparked national shock and mass protests, mobilizing Serbians against the normalized gun and weapon ownership in the country. Serbian media tended to sensationalize their reporting, and authorities shared dramatic details at press conferences. After this chaotic coverage, the podcast offered listeners an alternative approach, much more measured in tone and format, which the CINS team believes drove the podcast’s success: Miodrag explains that the podcast reached more than two million listeners, adding that promoting the podcast on TikTok with titled excerpts proved a successful way to reach audiences. Packaging their TikTok posts in a Hook, Value, + Call to Action format has also yielded good results for reaching more viewers.

“What distinguishes CINS from other investigative centers is that they often deal with topics that affect the common person, and have a good interaction with the audience.” — Tamara Filipovic, Independent Association of Journalists in Serbia (NUNS)

“Their podcast is really different from all currently available media podcasts,” says Filipovic of NUNS. “That kind of connection with the voice you listen to is much stronger and longer-lasting and somehow moves more people than the written word,” Šarić says, adding that this is “very important for CINS, considering that there is a great saturation in Serbia when it comes to bad news, that people are already tired and bitter, and that it is very difficult for them to process such difficult topics.”

CINS has also developed a video game called Good, Bad, Corrupt to present a complex and seemingly dry topic — public procurement — in a novel and engaging format. To create the game, they used open-source code with help from Journalism++ and worked with an external developer to customize it. The game has people “play” a corrupt city manager who has to keep their job — and not get caught — as they try to balance ethical and legal hurdles while maintaining support from businessmen and politicians. The ethical dilemmas a player encounters are based on real examples.

“The topic of public procurement is generally very boring and the term repels people,” Šarić notes. “But the largest part of citizens’ money is spent through public procurement, and that is why it is a very important topic, and this is a more innovative way to approach it.”

CINS also covered the environment in Serbia before the visibility of the topic became more widespread, which has helped them report on current issues. Today, it is much easier to go talk to people about these kinds of issues, says CINS Deputy Editor-in-Chief Dina Đorđević, who has covered questionable profits and pollution from hydropower plants and produces CINS documentaries on environmental crime, such as the recently published Taken Land, about the state seizing forests and farmland to make way for Chinese-built mines.

Tamara Filipovic of NUNS says this kind of forward-thinking approach is what sets the site apart: “What distinguishes CINS from other investigative centers is that they often deal with topics that affect the common person, and have a good interaction with the audience.”

Deset medijskih sporazuma za „zajedničku budućnost” sa Kinom, zemljom cenzure i progona novinara

Deset medijskih sporazuma za „zajedničku budućnost” sa Kinom, zemljom cenzure i progona novinara Filmovi o novinarima i za novinare

Filmovi o novinarima i za novinare Vučić i Tramp: Netrpeljivost prema medijima i podrugljivo odbacivanje drugačijeg mišljenja

Vučić i Tramp: Netrpeljivost prema medijima i podrugljivo odbacivanje drugačijeg mišljenja

Ostavljanje komentara je privremeno obustavljeno iz tehničkih razloga. Hvala na razumevanju.